A simple remark was the catalyst for a thought-provoking collaboration between a group of teachers, educators and geoscientists. A chemistry teacher expressed some of her frustrations about teaching the Leaving Cert chemistry syllabus. She noted that many processes are presented in isolation, and it often feels like her topics are disconnected from other subjects and real-world applications. She wanted her students to see the bigger picture. The geoscientists in the group asked what specific processes she thought could benefit from more interdisciplinary connections and our research idea was born.

At one point, we considered using lithium extraction, given its relevance to sustainability and the growing need for batteries in green technologies and the EU Green Deal. This we felt would link in very closely to the new sustainability based curriculum that is introduced throughout the country. However, in the end, we decided to use petroleum distillation as our example, as it was already part of the current LC chemistry curriculum. This meant we could potentially pilot our scheme if we were successful, without needing to wait for the new curriculum to be integrated. Using petroleum distillation as a model to show how cross-curricular collaboration could work and linking it to other subjects like geography (exploring the global distribution of natural resources), biology (discussing the impact of pollution on ecosystems), and economics (considering the financial implications of resource extraction) was something we felt we could do with the knowledge we already had, we just needed to think differently and expand our mindsets. We also felt it would be a good model to show how cross-curricular opportunities already exist with the curriculum, without the need to develop something new and time consuming.

Our group’s objectives were to help students become more informed about the industrial exploitation of natural resources and its environmental impacts. An education expert who joined the group suggested that they focus on three key areas: developing students' dispositions, skills, and knowledge, ultimately empowering them to become more engaged citizens. The group also considered how an idea like this could serve as a model for how to approach the new curriculum’s emphasis on sustainability and cross-curricular collaboration.

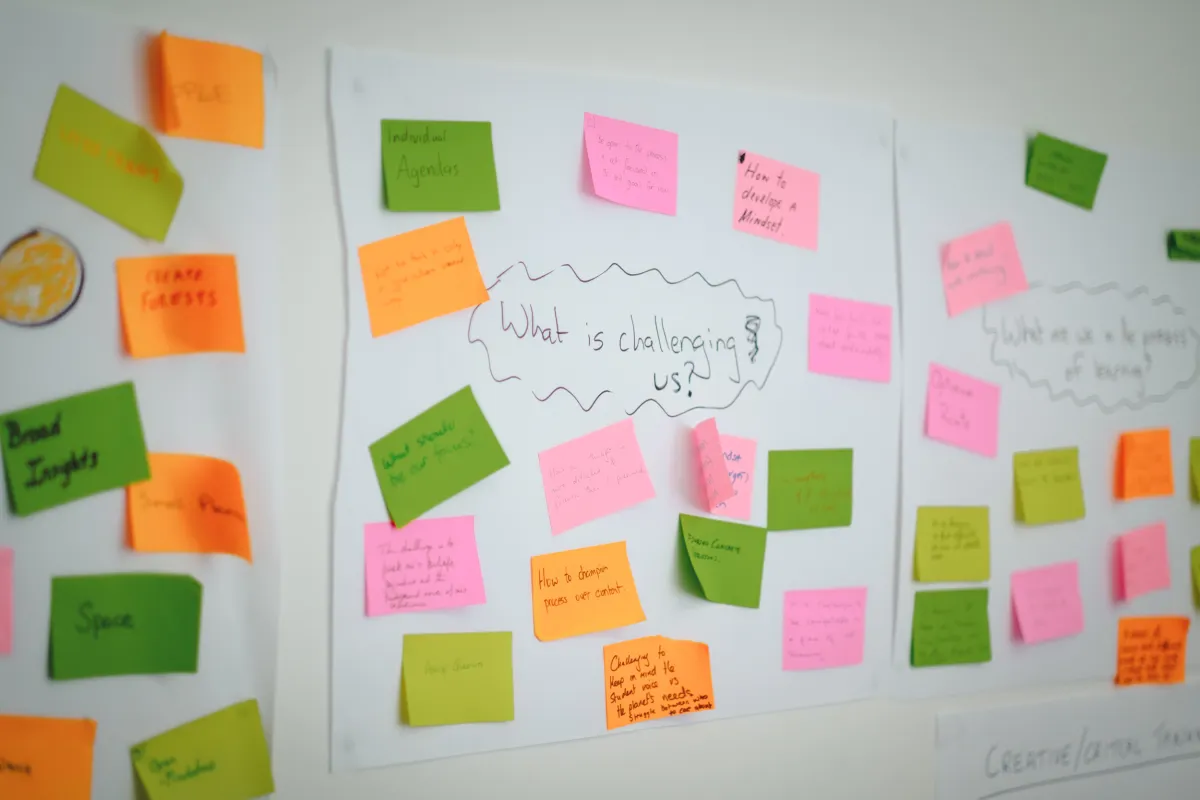

However, the project was not without its challenges. With only one active teacher in the group, there was a limit to how far we could push the project forward. We realised we needed more teachers from different subject areas to contribute if we really wanted to see cross-curricular teaching take off. We also quickly realised that one of the biggest obstacles to our collaborative project was a surprising lack of knowledge about what subject teachers are teaching. It became clear that we didn’t know the specifics of what was being covered in different subjects, nor when these topics were being taught over the two-year Leaving Cert cycle. Without a clear idea of when and where similar concepts were being introduced, it is very possible that we might be teaching the same concepts multiple times across different subjects. This opened up a broader conversation about the importance of communication and planning between teachers across different departments. If our cross-curricular collaboration is to be successfully implemented, we need to be aware exactly what is being covered. Having this information would allow us to coordinate more effectively, ensuring that students were encountering related concepts, in a way that built on their prior knowledge rather than simply repeating it.

The group began to explore the possibility of creating a shared calendar, placed somewhere prominent eg. in the school staffroom, where teachers might briefly outline their key topics for the upcoming term. This would make it easier to identify opportunities for collaboration, ensuring that teachers could work together to deepen students’ understanding rather than repeatedly covering the same material in isolation. We could create a more cohesive learning experience for students, where knowledge was organically shared between subjects. The group went on to discuss the possibility of using Professional Development hours to give time for teachers and educators to develop an incentive like this in their own schools, so that doing something innovative like this wouldn't be yet another thing that teachers have to do outside their teaching hours. If the department allowed schools to self-certify CPD hours for teachers who worked together on projects like this, this might be an easy and effective way to encourage more innovation and exemplary teaching within schools. If more “officially” backed support was needed to certify the time spent developing these types of initiatives, then perhaps University College Dublin could offer some form of official backing.

We know there’s more work to do and more input needed to develop this idea further as our idea didn’t develop as much as some of the ideas from the project, but there’s real potential to do something good in this space. Communication and coordination between teachers are essential to making cross-curricular collaboration work. Without it, we risked missing the chance to create richer, more interconnected learning experiences for our students.